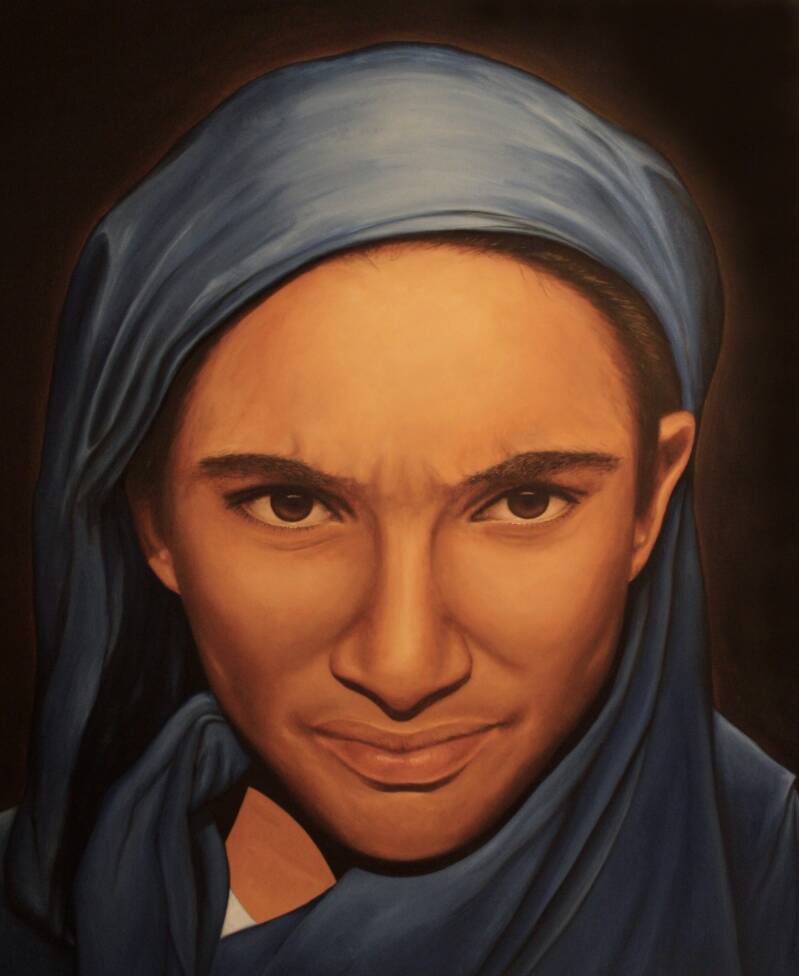

The African bride

2021. Oil on canvas 240 x 190

€ 5.900,-

Maria from Senegal is a young woman who was threatened with honor killing for homosexuality in her country. After fleeing to Europe, she met the love of her life Zoë.

Now, they can be married and live happily ever after..

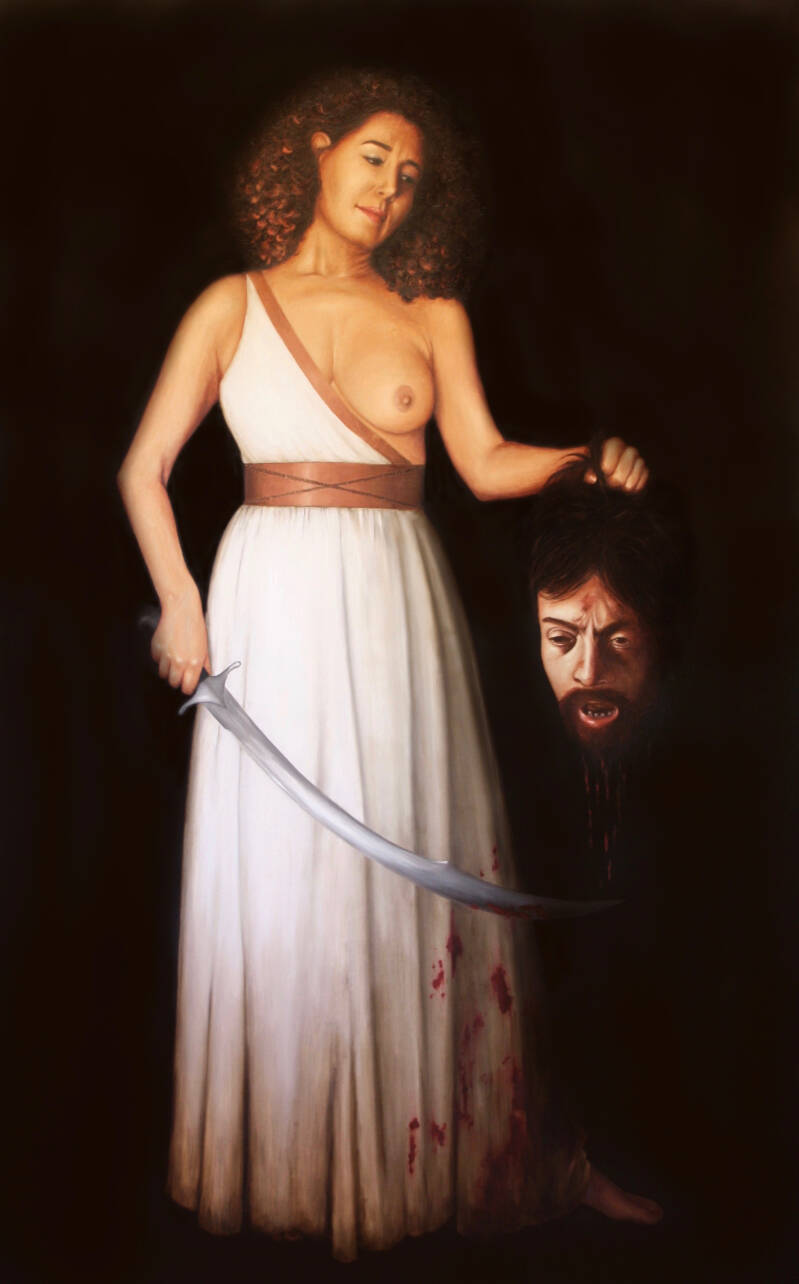

#metoo: Davide with the head of Goliath

2020. Oil on canvas, 195 x 125 cm.

€ 4.100,-

I hate violence. I wish we would be a more peaceful species, and less inclined to dominate and suppress other beings. Ironically, the paradox is that sometimes violence is needed to avoid violence, or to simply defend ourselves under attack.

In classical art the theme of the oppressed fighting his suppressor was painted a number of times by Carravagio, using the David & Goliath figures. In his ‘David with the head of Goliath’ we see David who beheaded Goliath and is looking down on him not with triomf but with compassion, a man who didn’t kill out of hate or rage, but because he wouldn’t be oppressed. I wanted to use the theme in this painting as a metaphor for the position of women today. For woman emancipation, so much is accomplished and yet there is so much left to do.

The beheaded goliath in my painting doesn’t stand for ‘man’ but for the patriarchy system both woman and man are the victims of. A system that evolved over thousands of years, that we are all part of, and that has to change for everybody’s sake. The Davide in my painting is a woman who shows the strength and compassion, the feminine power we need to change this system. Especially with the rise of alt-right movements worldwide we must make sure our daughters and granddaughters don’t end up as handmaids. We have to be vigilant not to let achievements slip away, and stay firm..

The head of Goliath in my painting is a copy of the original Caravaggio painting, the model for ‘Davide’ is Kaouthar Darmoni, one of Hollands most prominent and inspiring contemporary feminists.

#BLM Time to throw those chains off

2020. Oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm.

€ 2.100,-

When it comes to the matter of racism, all to often in discussions it all seems to turn around the question who is a racist or not. Nobody wants to be a racist; even the most extremist racists call themselves ‘race realists’.

But I think we are all somewhere racists, in most cases not because we want to, but because we’re all part of a system that that has evolved over the centuries in to a system where people with different skin colors are valued differently, even by themselves.

And most of the time we don’t even notice it because it happens unconsciously..

It can be a teacher who, without realizing, encourages some kids a little bit more than others, or a recruiter’s ‘gut feeling’ saying things about the capacities of one applicant or another..

Unconscious belief systems are hard to change, to do so we have to be honest and look at ourselves; question why we think or feel something about another person.

The Black Lives Matter movement helps to create awareness -it’s time to throw those chains of history off!

A little pietà..

2019. Oil on canvas, 130 x 120 cm.

€ 1.100,-

We always have a lot of attention for historical suffering; why

is there so little compassion for today's?

SLAVERY IN OUR TIME:

Definition of slavery:

A person being held against their will and forced to do labor under threat of violence

or some other form of abuse like denial of food.

The person has no rights and is considered property.

We tend to think that slavery is something of the past, from the heyday of European colonialism, a dark period in history.

In fact slavery has always existed and still exists worldwide today and on a very large scale; hidden in plain sight.

Slavery, not to be confused with exploitation, which is even way more common, concerns

over 40 million people today, according to estimations by organizations such as Amnesty International. About 70 % of them are women, 25 % children.

It’s present in the supply chains of almost all goods produced, from mining to the agricultural

industries and factories and there where services are provided by ‘unskilled’ workers such as sex workers or domestic servants.

Most common is ‘bonded labor’: poor people desperately looking for work borrow money to pay traffickers for a promised job abroad. Once at their destination their passports are taken away and circumstances are completely different than promised. They find themselves trapped and they cannot leave until they pay off the debts they owe to their traffickers. But often it’s hard to pay of the debts, as they can be charged for ‘costs’ for food and shelter, bigger amounts than their salary. That way, the debt can even grow.

Other forms of slavery are forced marriages, child soldiers or descent-based slavery, where people are born into slavery because of their parents debts, or their class or caste.

It’s present everywhere where poverty makes people vulnerable to be trapped in slavery or slavery-like conditions,

in a world economy depending on cheap labour and craving for profit.

In the days of institutionalized slavery, a slave was seen (and kept) a bit like we see cattle today;

good slaves were expensive but worth the investment.

Today, you can buy a slave for a few hundred dollars on the slave markets in Libya, or have them for free; people are just abducted from the streets

or stolen out of their villages, children given away by their parents that can’t provide for them or pay for their marriage dowry.

As consumers, we are on the other end of these supply chains; since we often don’t

know where the things we buy come from, we all buy goods that are at least partially produced by slaves.

The cobalt in our smartphones, computers and cars is most likely extracted from the Congolese mines by children under horrible conditions.

In Xi-an, the Chinese government detains 1,8 million Uyghur people in slavery-like conditions; they are set to work in on the cotton fields where 20 % of all the cotton in the world comes from, or in the many factories that big brands such as Nike, Zara, Adidas, Ikea, H&M, Volkswagen and many others have in the Xinjiang region to take advantage of the low costs for labor.

Off course the profit they make by doing so doesn’t make your clothes any cheaper but goes to the brands and their shareholders.

But as consumers we also have the power to demand from the brands and suppliers a responsible business conduct and transparency.

By being aware of the situation and favoring responsible produced goods over others when possible, brands will have to change their conduct if they want to sell their products.

Let’s end these barbaric practices and take ourselves out of the dark ages where slavery is still the fundament of our economy, our society.

INDIRA, RAJASTHAN, INDIA.

Indira was forced into marriage with a 38 year old man when she was 15.

The practice of forced marriage, (not to be confused with arranged marriage) is widely spread in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Approximately 15 million woman live in forced marriages under conditions that meets all the conditions to be defined as slavery.

In India, woman are considered to be of so little value that when a girl gets married, the girls father has to pay a dowry to the family that takes the girl as wife for their son.

For poor families, this is a heavy burden. But the younger the girl, the cheaper the dowry, therefore very poor families often see themselves forced to marry their daughter at very young age, even ‘promise’ them as a baby.

Sometimes, they simply give them away if somebody comes along that offers to take them ‘for free’. In that last case, the girl is usually taken away to be sold for prostitution or any kind of labour.

Once married, the girl is exposed to forced sex, pregnancy, motherhood,

and domestic or other labour and is often treated bad. Being considered possession of their husbands and his family, they have no realistic possibility to escape.

Disclaimer:

Looks are changed to protect Indira’s privacy. Any similarity with an existing person is coincidental.

2020. Oil on canvas, 110 x 90 cm. € 1.100,-

JOACHÍM, PERU

Joachím’s parents were killed on their farm by members of a Peruvian drug cartel and

Joachím was left with his cousin, who sold him to a goldmine at the age of 14.

He and his fellow-victims chew coca leaves non stop to make the work bearable.

Slavery and slavery-like practices are very common in de mining sector.

From coal, precious metals, to rare metals as cobalt, the mining industry is huge.

In Congo, where most of the cobalt is extracted for brands as Apple and Microsoft to

be used in smartphones, and computers, children as young as 7 years old work

in life-threatening conditions.

They work 12 hours a day, in intense heat and dust, carrying backbreaking loads, without masks or gloves, and subjected to violence, extortion and intimidation.

Dislaimer:

Looks are changed to protect Joachím’s privacy. Any similarity with an existing person is coincidental.

2020. Oil on canvas, 110 x 90 cm. € 1.100,-

AICHA, SYRIA

Aisha was a Syrian housewife living with her husband in Halfaya and working part-time as a secretary when the civil war broke out in 2011. Life became harsh, but it was only after 6 years of war when there was heavy fighting in Halfhaya and they had lost already family and friends they decided to use their last savings to try to escape. Their town being close to the shore, they trusted their savings to someone who’d help them escape by boat.

A storm hit their boat and 12 people drowned, among which Aisha’s husband.

Aisha and a few others were picked up by the Libyan coast gard and brought to a

‘refugee camp’ where their papers were taken from them.

A few weeks later, Aisha was sold at the slave market to a farmer.

She was forced to pick tomatoes in the burning sun every day for long hours.

Disclaimer:

Looks are changed to protect Aïcha’s privacy. Any similarity with an existing person is coincidental.

2020. Oil on canvas, 110 x 90 cm. € 1.100,-

DANG, CAMBODIA

After watching his younger siblings go hungry because their family’s rice patch could not provide for everyone Dang accepted a trafficker’s offer to travel across the Thai border for a construction job.

It was a chance he had to take. But once arrived he was captured by armed man and herded

with six other migrants up a gangway onto a ship. It was the start of three brutal years at sea.

The fishing industrie in South-east Asia is notorious for its slavery practices.

Sea vessels often stay at sea for years, far from the reach of authorities.

In interviews those who managed to flee or were freed recounted horrific violence: the sick

cast overboard, the insubordinate tortured or brutally murdered.

Disclaimer:

Looks are changed to protect Dang’s privacy. Any similarity with an existing person is coincidental.

2020. Oil on canvas, 110 x 90 cm. € 1.100,-